30 Jan A Million Ways to be a Good Father

By Mark Lim

I was with a good friend in Fraser’s Hill Malaysia, and he was skipping stones across the waters at the waterfall. I tried to follow him, but failed miserably. My friend learnt to skip stones from his father when he was younger. I wished my father had taught me how to skip stones.

But in truth, it wasn’t so much the lessons on skipping stones that I desired, but the presence of a father.

The pain of an absent father haunted me all my life—from the time my parents separated when I was 3, through childhood, adolescence and early adulthood years. It still affects me today.

I am completing my postgraduate studies in counselling, and one of my final assignments is to write a paper on a traumatic issue. I chose to write about my parents’ separation and divorce. The following extract describes a self-defeating pattern that I have had to deal with:

“There is much societal expectation that husbands and fathers need to be able to perform physical tasks. For instance, husbands are expected to help their wives in the house such as by fixing light bulbs and repairing spoilt appliances. As for fathers, they are expected to be the ones training children in physical activities such as sports.

“I feel inadequate in both these areas. This has led me to believe that my inability to perform such physical tasks has affected my ability to be a good husband and father.”

My two sons are very different. Unlike their father, they love sports and everything to do with the outdoors. My older son moves like lightning each time he races in the fields; and my younger son can almost pass off as a champion gymnast, even at the tender age of 5. In contrast, I was the boy who struggled year after year to pass the 2.4 km fitness run; the one who fell from the monkey bars at age 14, and ended up in a cast.

In counselling, we are taught to ask 4 questions that would help us understand and help our client:

- What is troubling the client?

- What is causing the problem?

- What is missing? and lastly,

- What is needed?

If I were posed the last question, part of my answer would be “If I want to re-write my trauma script of my father abandoning me and leaving me without a healthy role model, I have to change my mindset and alter the self-defeating patterns that have been wrecking havoc inside me. I have to choose to change my perspective that I cannot do many physical tasks because of my father’s absence.

While this may not be easy, I believe that I have been trying to do more physically challenging tasks, even if these may frustrate me. I also need to change the notion that I am a good husband and father only if I am adept at physical tasks. There are other ways to be a good husband and father, and I can excel in some of these other ways.

We will always carry the traumatic events of our past unless we intentionally re-write the script.

I may never be the father who takes his son to the soccer pitch each week to practise kicking and scoring a goal. I may never be the father who takes apart a household appliance and shows his son how to put it back again. I may never be the father who talks to his son about all the different types of cars.

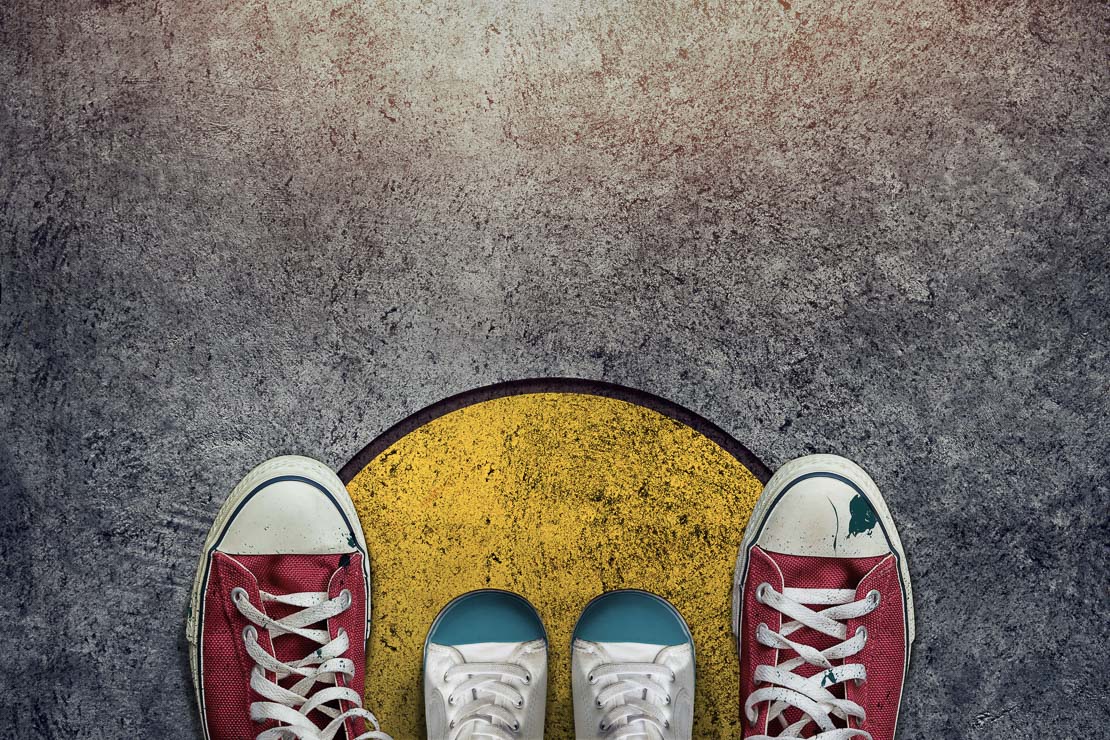

But I am the father who spends time every evening playing a board game or two with my son. I am the one who whips up a picnic breakfast with my son and takes him out for a long walk in the park.

I am the father who teaches my son about bullies and helps him to resolve his own battles. I am the one who corrects his mistakes, and encourages him to choose the right thing even when everyone says otherwise.

I am the father who is always there in good times and bad; to celebrate and affirm, but also to comfort and hug.

I may not be a perfect father by any societal standard, but I have learnt that there are a million ways to be a good father. And I will do my best to be there for my son, day by day to pick him up when he falls.

Mark Lim is consultant and counsellor at The Social Factor, a consultancy and counselling agency which conducts training on life skills such as parenting, mentoring and special needs. He and his wife, Sue, co-write a parenting blog, ‘Parenting on Purpose’, where they chronicle the life lessons from parenting two young boys aged nine and seven. Mark’s original article can be found here.